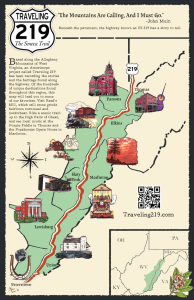

Pickaway

Pickaway and its surrounding area was long inhabited by the Seneca tribe of Native Americans, and their main pathway through the mountains was roughly the same route that 219 follows today. Pickaway was also known as “Pickaway Plains”, and though the exact origin of the name is not fully clear, the Picqua tribe of Native Americans was one way or another most probably the source of this unique name.

Pickaway and its surrounding area was long inhabited by the Seneca tribe of Native Americans, and their main pathway through the mountains was roughly the same route that 219 follows today. Pickaway was also known as “Pickaway Plains”, and though the exact origin of the name is not fully clear, the Picqua tribe of Native Americans was one way or another most probably the source of this unique name.

The local school at Pickaway was the site of the first Corn Club in West Virginia, established in 1907. The Corn Clubs began in the Midwest as an effort to educate rural youth about contemporary, scientific methods of growing corn. This movement was essential as it later became 4-H and Future Farmers of America to help encourage young farmers.

The first known white settler of Pickaway, Joseph Parker and his family came to the area between 1775 and 1785. William Hawkins from Philadelphia and John Gray, also from Pennsylvania, were other early settlers who established good-sized farms in the area. Gray also constructed a log fort that would become known as “Pickaway Fort” or “Thompson’s Fort”.

The community of Pickaway is also important as the nexus of 219 and the Creamery Road, or Route 3 headed west. Of the early families that came to the area, many live on today and in some cases own the same farms that their forefathers long ago first tamed from the thick, wild, forest, which covered these rolling plains. The Campbells, the Parkers, the Becketts are still all represented in the community to this day.

Along 219, just south of the intersection with Route 3 was the business center of Pickaway, with a church, store, and school. There were also a grist mill and a blacksmith’s shop in this small community. The mill operated a diesel-powered engine for the grinding of grain as there was no water source nearby; like most mills of the period, the construction was timber-frame of what is known as a husk frame design. This approach provides for a far more robust and sturdy inner frame that can withstand the level of continued vibrations produced by the millworks. Attached to the mill was a blacksmith’s shop

The general store served as the center of neighborly fellowship and informal meetings. In some cases, more formal meetings also were held there: in Pickaway for example, Hazel Shrader’s records indicate that local men met at the store one evening to talk over the planned route of the electrical service coming to the community in 1927.

Today, some Pickaway residents work in Greenbrier County or in the local schools or the B.F. Goodrich plant near Union, but many who even have other primary occupations also keep small farms—some of which have been passed down from father to son for decades. Most farming families in Monroe County and many who may not even have working farms keep large, serious gardens and garner much of their food from them.

Beef cattle has become the main livestock found in Pickaway and all of Monroe County today, however, dairy cattle, goats, and turkeys are still important production animals while many families keep chickens and possibly hogs for smaller-scale or personal consumption production. The lay of the land—rolling, in places even mountainous though not so much as the lower part of Monroe County—in Pickaway makes for difficulty in raising large amounts of fodder crops, though corn and hay are both commonplace.

Sheep were, through the 1960s, a staple animal of farms in Monroe County but seem to also have faded from popularity since then. Part of this is due to changes in the use and thereby pricing of wool and also the spread of coyotes into the county from the west, as they are prolific predators of sheep but not of cattle. However, Dave Bostic and a few other current farmers in Pickaway have once again resumed sheep production.

In 1999, in recognition of the unique value and high level retention of contributing structures, the Pickaway Rural Historic District was added to the National Register of Historic Places under rural historic districts with essential national value due to their contributions to the agricultural history of America.

This article is written by Mike Walker, guest writer with the 219 Project. His grandmother, Mayo Lemons, still lives in Pickaway.

Category: Lewisburg to Rich Creek