Lewisburg Lovesong

This article is by guest contributor Jeffrey Kanode:

Caressed all around by the eternal arms of soft blue Allegheny Mountains, with lush green farmland surrounding it from every direction, Lewisburg is a farmer’s town. With aging hippies from New York and New England operating their avant-garde art studios, health food stores, and organic food restaurants, with those businesses providing the downtown with a renaissance unique to southern West Virginia, Lewisburg is a bohemian’s town. With a mass Confederate grave shaped like a cross on a ridge overlooking town, with the boys in gray routinely winning the battle raging downtown every May for the Battle of Lewisburg reenactment, even though even the historical markers in town acknowledge the Union won the battle, Lewisburg is a Johnny Reb town. With a slave cemetery in a meadow below the Confederate cemetery, overrun with weeds; with the historical African American Methodist church falling in disrepair, Lewisburg is a reckoning town.

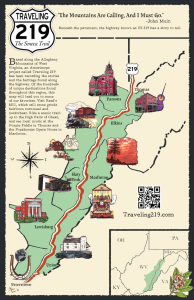

My family and I traveled US 219 for many years to get to Lewisburg from our home in Princeton. Every August we made the pilgrimage to the state fair, and it was a particularly holy visit in 1991 when Garth Brooks played, and the me who was then a cystic acne scarred teenaged boy grinned from ear to ear in the soft moonlight enveloping Fairlea, Lewisburg, and the state fair grounds. Many years later, in the spring of 2007 I traveled down 219 once again to arrive in Lewisburg, this time to stay, this time to call it my home. By then I was in the fellowship of the still-itinerating Methodist ministers, and Lewisburg was my new assignment.

The Lewisburg United Methodist Church is one of the largest Methodist churches in West Virginia, although Lewisburg isn’t considered one of the biggest towns, especially when compared to Huntington, Charleston, Parkersburg, Morgantown, or Clarksburg. LUMC, as the church members frequently call their church, dates its founding all the way back to Bishop Frances Asbury in the days when the gunpowder of the American Revolution was still hot. I was so proud to serve such a historic church, although I seriously doubted the actual accuracy of claiming Asbury’s visit to Lewisburg as the church’s founding. Just because Asbury prayed in someone’s parlor and preached under a tree, I always thought it a stretch to claim Asbury as the founder of the church. While I am sure the good bishop was enamored with the beauty native to Lewisburg, he was just passing through.

In so many ways, that Methodist Church in Lewisburg is a microcosm of the town. There were blue collar, middle class families in that church. There was old moneyed blue blood running through the veins of that church too: There were doctors and lawyers who owned large tracts of land that dated back 200 years in their families. There were artists and hippies: proprietors and patrons of the eclectic downtown. The church stood on a knoll overlooking the expanse of the downtown: For me that layout was perfect symbolism: the church was where I served and where I worked; all paths out of the church lead to the downtown where fresh coffee was always brewing at The Wild Bean and on some days a funky little jazz band was playing. While I loved the church and the work I was called to do, I also cherished escaping its walls to make my tactical retreat downtown where coffee and music, theatre and conversation would enrich my soul and sustain my spirit.

Something else happened in the Lewisburg UMC that could have been pulled straight out of Main Street, but Sinclair Lewis didn’t write this—I lived it. Because Lewisburg is a small town, but LUMC is –by West Virginia’s standards, anyway—a big church, an obnoxious, or beautifully poetic thing would often happen within those walls: A couple would be going through a divorce, and he would come to the 9:00 service, she would come to the 11:00 service; both would come to Sunday School and even attend the same class, but she would sit on one side of the table and he would be in the far corner on the opposite side of the table. They agreed to continue attending the church because the Sunday School and Christian education program for the children was second-to-none. It was, as I told my friends on the church staff: Big church, little town. It created its own messy, but messily human, and thus profanely holy, reality. Her lawyer and his lawyer sat just a few pews up from one another. The family court judge who would preside over the divorce hearing and even determine the custody arrangements for the children sat up in the choir loft, singing his heart out week after week, with a bird’s eye view of all this drama which would eventually play itself out and find resolution in his workspace. My own personal life got very intertwined with my professional life in the church: I became a huge dramatic player in the great play Big church, little town.

And it was all so Lewisburg.

Portraits of Robert E. Lee hung on the walls of professional, well-to-do, enlightened church members who became friends of mine.

The Old Stone Presbyterian Church hosted the entire Christian community of Lewisburg for Easter Sunrise service on Easter morning. The service was held on the grounds of Carnegie Hall—an exact replica of the one in New York City, funded with the same Carnegie dollars which built the one in NYC—and there we proclaimed and celebrated Christ’s resurrection with a string quartet and an erudite message about what Christ’s empty tomb means for us humans today. We did it all on the lawn where in the spring folks would sip wine and eat cheese listening to folk groups, blues singers, and jazz quartets playing Carnegie’s Ivy Terrace concert series. After the service, we would eat a hearty Easter breakfast together: It wasn’t the buckwheat pancakes and runny-in-the-middle eggs and biscuits and gravy I was accustomed to being a Princeton, West Virginia boy. No, Easter sunrise breakfast in Lewisburg was scrambled eggs and oysters. It is a true antebellum Southern traditional delicacy, and I loved it.

Only in Lewisburg.

Within the mecca of fine dining, antiquing, coffee shops and art galleries of Lewisburg, the Greenbrier Valley Theatre stood significantly, but humbly. Within those walls the theatre major kids and English major kids from every conceivable liberal arts college in the region answered their parents’ question, “Where are you going to find a job?” Within those walls professional actors riding a circuit which included off Broadway and occasional Broadway gigs found a season’s worth of work. Within those walls Shakespeare came to life again, and the Greenbrier Ghost caught her choked breath and spoke again. Within those walls children giggled to If You Gave A Moose a Muffin and many of those same children got to join their lucky (or uber talented) peer who got to play Tiny Tim in The Christmas Carol. Within those walls, would-be writers like me got to see their plays come to life in a yearly contest for amateurs, or dreamers. Within those walls the blue mountains surrounding Lewisburg didn’t feel quite so stifling: they felt protective, and nourishing of the spirit so alive there.

In Lewisburg I preached and wrote, I drank at the Wild Bean and at The Irish Pub. My trips to the Irish Pub I considered part of my religion because on the far wall overlooking the most secluded booth there were autographed pictures of two of my saints: John Paul II and John F. Kennedy. The Pub held trivia nights, and from teams called “Pastor Jeff and the Drunks” to “Twenty Five Years of Mud,” in honor of my friend Meredith’s twenty-fifth birthday, which we celebrated that night, playing Pub trivia, at Lewisburg’s Irish Pub, I had my share of winning streaks, and losing streaks.

It was all so Lewisburg.

In Lewisburg I courted and chased. In Lewisburg I wooed and was accepted.

In Lewisburg I married and divorced.

The streets of Lewisburg haunt me.

The streets of Lewisburg are still home to me.

There is Lee Street, again named after Robert E. Down this street the remaining Confederates who had escaped the slaughter of the Ohio Yankee’s artillery (commanded by future president Rutherford B. Hayes) retreated, and they wouldn’t stop until they got to Droop Mountain in far-off Pocahontas County. There is Lee Street where my near-mansion, three-story parsonage stood. There is Lee Street where I would walk my little stepdaughter from our parsonage to the elementary school, where she was in kindergarten.

And there is Hollowell Park where my dog Snoopy used to run. He used to sneak out the front door every time anyone opened it, and I would find him eating hotdogs people gave him at the little league games at Hollowell. The people didn’t know his name, but they knew Snoopy. If Snoopy escaped earlier in the day, before the evening’s little league affairs, he would make his way to the elementary school, much to the delight of my stepdaughter. He would hang out until recess, hiding in the bushes or under a bench. At recess then, he would come bounding out of the shadows, his little stubby legs just flying, as he raced to play with the children. One of the teachers—a faithful church member and my stepdaughter’s teacher, would somehow corral Snoopy into her classroom and call me to come and get him.

I am haunted by Lewisburg.

There are ghosts in Lewisburg. Some of them are my ghosts. Some of them are slaves’ ghosts. Some of them are Confederate ghosts. They are all ghosts who recognize the weirdness, the schizophrenia, the beauty, the holiness of the place, and so they do not leave.

Lewisburg will always be home to a huge chunk of my heart, a substantial peace of my soul.

Kanode is a Methodist Minister at Ona, W.Va., in Putnam county. Previously he was an Associate Pastor at Lewisburg’s United Methodist Church.

Category: Blog, Lewisburg to Rich Creek, Marlinton to Lewisburg