The Great Depression and THE guidebook of West Virginia

The Great Depression and THE guidebook of West Virginia

The Great Depression and THE guidebook of West Virginia

The book featured in the photo to the left is called West Virginia: A Guide to the Mountain State, published by the West Virginia Writers’ Project in 1941. It was written over seventy years ago during the Great Depression, and though most local libraries own a copy, most people who love and live in West Virginia have never even glanced through its pages.

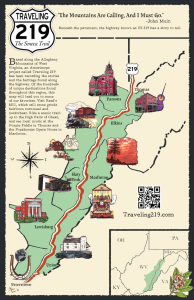

Dr. Jerry Bruce Thomas, author of An Appalachian New Deal: West Virginia During the Great Depression, traveled US 219 in 2010, speaking in Marlinton, Lewisburg and Union, WV. During this lecture series, Dr. Thomas led community discussions about the possibility of revisiting these materials for a modern day guide to West Virginia along US 219. The following article is from his presentation, the inspiration behind the Traveling 219 website:

The Federal Writers’ Project

The Federal Writers’ Project (FWP) was launched in 1935 as part of the Works Progress Administration (WPA), a New Deal relief program initiated by President Franklin D. Roosevelt during the Great Depression. The original writers’ project, an eccentric, quirky, and unwieldy venture, was funded entirely by the federal government with the primary goal of giving work to unemployed writers.

The WPA represented an effort on the part of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal to provide work relief for the unemployed. Roosevelt preferred federally-sponsored work relief rather than handouts for the many thousands of able-bodied workers who could find no work. For the aged and those unable to work, Roosevelt proposed Social Security, a system to be administered by the states. The Great Depression left some cities with unemployment rates up to 50%. In some West Virginia counties, this rate was even higher.

Even writers had to eat, so the WPA, which employed hundreds of thousands of blue collar workers to wield picks and shovels on construction projects, hired unemployed writers or would-be writers to apply their pens, papers, typewriters and inquisitive spirits to writing projects.

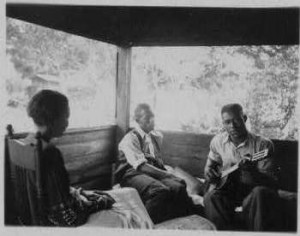

Zora Neale Hurston interviewing musicians Rochelle French and Gabriel Brown. Photo by Alan Lomax, 1935.

The writers put to work by the FWP include some of the twentieth century’s most celebrated American writers. Saul Bellow, Ralph Ellison, John Cheever, Richard Wright, Nelson Algren, Margaret Wright, Conrad Aiken, Zora Neale Hurston and Studs Terkel – as starving young writers in the depths of the Great Depression they all got jobs with the Federal Writers’ Project, a relatively small part of the WPA.

Not all of the 7,000 or so writers employed by the project became famous. But most worked hard at discovering and writing the history, geography, folklore and culture of their cities, towns and counties. A lot of what these writers generated unfortunately lies forgotten in the files of the Writers’ Project. Other parts of it had enduring consequences for state and local history throughout the country, particularly in calling attention to people and topics neglected in past histories and telling the story of how America had become a vast mosaic of ideas and culture.

To get a job with the Writers’ Project you had to qualify as both eligible for welfare (they called it the pauper’s oath) and offer some evidence of skill as a writer. It was a strange situation (as David A. Taylor put it, in Soul of a People). “Are you poor enough? Okay. Now, are you skilled enough?’ It was a Kafkaesque situation.” If they got the job, it paid about $20 per week in urban areas. In West Virginia, it paid less than that. The salary for a field assistant in Monroe County, West Virginia, for example, was $67.50 a month for a month of 130 hours. This sum helped to keep the wolf from the door—if it wasn’t a very big wolf.

The writers had no easy time of it. In addition to their low pay, they frequently had shortages of paper, envelopes, typewriters, equipment and travel allowances. Few of them would have owned cars, and getting around the area to cover their assignments could be a problem. They did a lot of walking.

The files of the West Virginia Writers’ Project contain little biographical material on the writers. Most were not well known. For instance, in Pocahontas County, West Virginia, most were former newspaper writers, reporters and schoolteachers. During the Great Depression, some believed that women should not work. All jobs should be reserved for family “breadwinners”—meaning the men. Some school districts even fired their women teachers, but the Writers Project was one of the work relief jobs of the time for which women could qualify.

The Federal Writers’ Project in West Virginia

The most tangible result of the Writers’ Project was a series of state guides, compendiums of folklore, history, geography and recommended tours. One of the last to be published, West Virginia: A Guide to the Mountain State, represents a pioneering effort to assess the state’s social and cultural heritage. The Guide’s recommended tours also provide a handy snapshot of the state of the state in the Depression Era of the 1930s. The West Virginia Guide became a hot political issue at the time. Some tried to stop its publication, but after more than 70 years it remains one of the best and most comprehensive books ever written about the state.

These researchers worked from 1935-1941 collecting a mass of historical, cultural, geographical, and anecdotal material about the state of West Virginia. They talked to people all across West Virginia, listening and researching the uncommon stories of America at a time when our country was searching for its own identity. The West Virginia guidebook provided some of the most striking descriptions of the roadside wonders, historical tales and travel destinations written about West Virginia.

The Guide not only gave the people of the state a readable addition to their literature, it also legitimized and authenticated the history of workers and unions, just as the New Deal legitimized collective bargaining and the unions themselves. Henceforth, histories of West Virginia included not only the frontier pioneers, Civil War heroes, state makers and business leaders, but also workers, their unions and accounts of those days when, as West Virginia State Director Bruce Crawford said, the pistol rather than the conference table prevailed in settling disputes among employers and employees.

Much of the research prepared by the local writers provided material for the state guide, but the county level got little attention in the Guide. In Pocahontas County, much of the effort of the writers went instead into the research and writing of a county history. On March 29, 1940, the Pocahontas County Board of Education and the County Court jointly agreed to sponsor the county history and to pay the publication costs.

In 1941 and early 1942 the local writers were already preparing writing for the history underway. Writers such as Roscoe W. Brown worked on the chapter “natural setting.” Rella F. Yeager wrote about Edray, Hunterville, and Green Bank Districts. Nellie Y. McLaughlin wrote about Dunmore, and provided materials for the chapter on early life and occupations. Richard Dilsworth wrote a draft of chapter IV, “The People.” Juanita F. Dilley of Clover Lick probably covered more topics than any other Pocahontas writer. In addition to writing a comment on local names, Dilley contributed to Chapter 4 material on the Civil War and Chapter 5 on “Early Life and Occupations.”

The research for the county history included much information about participation in wars, going back to the revolutionary war, including a list of 42 men of Pocahontas who fought in the Revolution and 12 in the War of 1812. One poignant story is about Lt. Robert Kerr, son of county resident James Kerr, who graduated with distinction from West Point in 1898, a source of great pride to his family and to county residents. Ordered to the Philippines in 1898 at the time of the Spanish-American War, he died on a troop ship before he got there and was buried at sea. A marble monument in his honor was erected in the Kerr cemetery, near Boyer.

While the Pocahontas writers were busy making progress in their tremendous effort to produce a book about the county, the nation was attacked at Pearl Harbor and the United States entered into the worldwide conflict that would consume it for the next three years. As unemployment declined with the crisis of the Second World War, Congress called for an end to New Deal programs, and FDR said it was time for Dr. Win the War to take the place of Dr. New Deal. With the sudden shutdown of the WPA in March, 1942, the work of the Pocahontas County writers was left incomplete. In an inventory of the work as the WPA closed down, State Director Bruce Crawford listed materials completed in the county history project, but concluded his report bluntly: “Wordages sent to publisher—none.” Though most of the program–including WV’s–shut down in 1942, the agency’s official demise came in April 1943 as a small number of employees who had basically worked the graveyard detail quietly left their office in Washington on April 27.

Despite the controversies, the unfinished projects, and the relatively brief existence of the Federal Writers’ Project, it has left an enduring legacy that continues to influence and inspire new generations of Americans. The FWP helped foster a generation of struggling writers, during some of the nation’s hardest times, names still recognized for their literary and cultural contributions. It also enabled those less known writers to work and publish through the Depression, leaving later generations with invaluable works of history and literature such as the American Guide Series. Both the published and the unpublished work of the Project stand as a testament to the nation at a critical moment in its history.

Photo by Dorothea Lange, Napa Valley, CA, 1938. “More than twenty-five years a bindle-stiff. Walks from the mines to the lumber camps to the farms.”

David M. Kennedy has written that “it was [as] if the American people, just as they were poised to execute more social and political and economic innovation than ever before in their history, felt the need to take a long and affectionate look at their past before they bade much of it farewell, a need to inventory who they were and how they lived, to benchmark their country and their culture so as to measure the distance traveled into the future” that would be very different from the past.

–Dr. Jerry Bruce Thomas is Professor Emeritus from Shepherd University. He is the author of An Appalachian New Deal: West Virginia in the Great Depression, An Appalachian Reawakening: West Virginia and the Perils of the New Machine Age, and “The Nearly Perfect State: Governor Homer Adams Holt, the WPA Writers’ Project and the Making of West Virginia: A Guide to the Mountain State.”

Category: Elkins to Marlinton