Ramps-Are we Sustainably Harvesting Them?

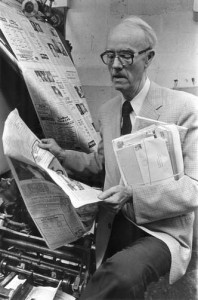

photo by Mike Costello. Note: This article is a second installment about some of the ongoing issues surrounding wild ramp harvests. [For the first article, click here]

As a rule, ramps pack a very strong flavor, and they generally cook well any way that you would use onions, garlic or spinach. In NYC the new wild food craze has ignited obsessive Twitter followings for ramp enthusiasts, leading to an even greater popularity among urban foodies, most of whom have never even set food inside a ramp patch.

Over the last 3 years or so, the springtime emergence of ramps at farmers markets and at gourmet restaurants throughout NYC has attracted a very obsessive social media following. See Ramped for Amps on Twitter. A new ramp fest in NY began in 2010. An upcoming new book about farming crops like ramps and mushrooms in the forest is set to be published this fall from Chelsea Green Publishing. I talked a bit with one of the authors, Steven Gabriel, who stressed that this trend is indeed on the rise, despite the threats that face ramp populations.

Whereas ramps have been a part of gourmet menus for about 15-20 years, more consumers have been drawing towards this trend of seasonal-foods since around 2010 or 2011. The popularity of ramps doesn’t seem to be abating (due in part to ramps’ fleeting seasonality, the excitement is fresh again each year). In late March and early April when ramps first go on sale at farmers markets, they are snatched up in almost lightning speed. This is especially true during the first few weeks of the season in late March and early April. There is not a lack of people who want to buy ramps. But finding them, and sustaining them, is increasingly difficult.

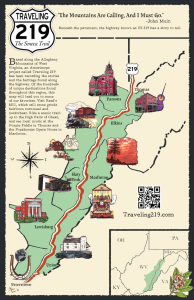

Entrance to the highland scenic highway, outside of Richwood. Technically, the Monongahela National Forest prohibits commercial ramp foraging on their property, though this is difficult to enforce. photo by Josh Stevens.

As the popularity continues, even some chefs and consumers are beginning to worry about ramps. These chefs and ramp enthusiasts would definitely suffer if ramps were overharvested (as they were in Quebec, where commercial foraging has been banned since 1995), not to mention the harvesters who have been digging them for years (many of whom support their families all spring on this income).

In Richwood, the ramp festival each year has become their main source of fundraising for the community. Since newspaperman Jim Comstock helped Richwood become the Ramp Capitol of the World when he notoriously put ramp ink in an April issue of the Richwood News Leader, the festival has continued to draw thousands of tourists each spring. If ramps went away, or if the Monongahela National Forest began heavily enforcing the ban on commercial digging on their property, the town of Richwood would seriously suffer.

If ramps disappeared, it would end a 300 year tradition of Appalachians foraging wild ramps in the woods, and white settlers inherited these practices from Native Americans before that.

Here in the Monongahela National Forest, people say there are still plenty of ramps to be found, but they are receding deeper into the forest where road access is very limited. “This indicates that ramps are being affected by digging,” says Jim Chamberlain, a researcher with the United States Forest Service.

Research suggests that ramp plants can take as many as 8 years before they are mature enough to sustainaby harvest them, and that even then only about 10% of the plants should be harvested so the patch to continue. Ramps are bulb dividers, rhizomes, like ginger or ginseng, and are very sensitive to mass-harvesting. Native Americans used to only cut off the green ramp tops, and a new movement in NY is trying to promote this type of green-harvesting. However, there is far more demand for the bulbs that the greens.

This year, The New York Times reported that one of the first restaurants in NYC that served ramps this year was Tarallucci e Vino, which got its early ramps from an unnamed source in South Carolina. I asked Chef Welch if he would consider buying ramp greens without their bulbs, and he said it would be a more difficult sell.

“The greens have a very short shelf life and the flavor concentration tends to be in the bulbs themselves, not the greens. I do use the greens but they would not be the same if that were the only part we used. I wouldn’t be opposed to buying just the greens to bulk up pesto or ramp butter but it would be used in conjunction with the bulbs, never without them.”-Andrew Welch, chef at Tarallucci e Vino.

And while there are only a handful of studies about the effects of ramp harvests on populations, there is some indication from the scientific community that we should be erring on the side of caution. This includes a study in 2012 from St. Lawrence University. Other researchers who have contributed considerable evidence that we need to better protect wild ramp populations includes Dr. Jim Chamberlain, researcher with the United States Forest Service Dr. Jim Chamberlain, Janet Rock, botanist with the National Park Service, and Dr. Jeanine Davis, assistant professor in the Department of Horticultural Science at North Carolina State University. Dr. Davis was part of a long-term studies about ramps that led to the Great Smokey Mountain National Forest banning commercial digging on their property in 2002.

At the US Forest Service’s Southern Research Station in Blacksburg, Virginia, Dr. Chamberlain built a raised bed for growing wild ramps, using bulbs from Facemire’s farm. With about 30-40% shade and moist soil, ramps can be sustainably cultivated. Both Burkhart and Chamberlain stress that this is a plant that requires patience. Ramp patches take about three years after the bulbs are planted until they are mature enough to harvest. If you plant seeds, it can take up to two additional years before the ramps even begin to sprout. As long as you have the appropriate conditions, with moist soil and about 30-90 percent shaded area, you can enjoy the benefits of growing wild ramps in your own backyard.

“If you choose to grow them, there’s no fertilizer. They’ll do their own thing,” says Glen Facemire. “They’ll grow in different soils. They’re amazing. I’m asked the question, ‘well are these ramps that you have on the ramp farm like wild ramps?’ They are wild ramps. We just got them on the different side of the fence now. We’ve got them in shotgun range now.”

Here are more links to growing wild ramps:

http://www.ces.ncsu.edu/hil/

If you want to grow ramps from bulbs, Glen recommends ordering them in January. Delaware Valley Ramps, in Pennsylvania, suggests ordering their ramp bulbs in late fall or winter.

Glen Facemire’s Ramp Farm : P.O. Box 48, Richwood, WV 26261. Phone: 304-846-4235. Email: rampfarm@frontier.com

Delaware Valley Ramps : Steven Schwartz’s farm is located in the little town of Equinunk, PA on the banks of the upper Delaware River. Phone: 570-224-0580. Email: smsinc@panix.com

Ramp Festivals: For a complete list of ramp festivals, click here to visit the King of Stink’s website.

Besides Richwood’s Feast of the Ramson, here are two more ramp festivals which are also planned on the same day as Richwood’s feast, Saturday April 26th. Maybe someone can hit all three in one day:

Helvetia’s Ramp Supper: April 26. Click here for Helvetia’s website.

Elkins Ramps and Rails Festival: April 26

Ordering Fresh Ramps: Please note, when ordering ramps it is always best to buy from a local ramp dealer. Check with sellers that the ramps you are buying have been harvested sustainably.

Wild Purveyors : 5308 Butler Street, Pittsburgh, PA 15201. Phone: 412-206-9453. (they also forage wild mushrooms and sell other wild foods and wild food products)

Bruce Donaldson’s Four Season’s Outfitters Store : 190 Middletown Rd. Routes 39/55, Richwood, West Virginia, 26261. 304-846-2862.

Bruce Donaldson’s Four Season’s Outfitters Store : 190 Middletown Rd. Routes 39/55, Richwood, West Virginia, 26261. 304-846-2862.

Ramps from Elegance Distributors, grown in Michigan.

Elegance Distributors : 106 Main Street, P.O. Box 275, Eaton Rapids, Michigan, 48827. Call Claude Ghafari or Burdette Pombier 1-800-487-6157.

Sources: Special thanks to these researchers for providing information about conserving and harvesting wild ramps:

Jim Chamberlain, Ph.D. Phone: 540-231-3611. Email: jchamberlain@fs.fed.us. USDA Forest Service, Southern Research Station. 1710 Research Center Drive, Blacksburg, VA 24060. “If we don’t figure out a way to manage them, they’ll be gone,” says Chamberlain. “If there are no more ramps, there will be no more ramp festivals.”-quote from an article by the Washington Post. Click here to read the article.

Jim Chamberlain, Ph.D. Phone: 540-231-3611. Email: jchamberlain@fs.fed.us. USDA Forest Service, Southern Research Station. 1710 Research Center Drive, Blacksburg, VA 24060. “If we don’t figure out a way to manage them, they’ll be gone,” says Chamberlain. “If there are no more ramps, there will be no more ramp festivals.”-quote from an article by the Washington Post. Click here to read the article.

Eric P. Burkhart, PhD. Program Director, Plant Science, Shaver’s Creek Environmental Center. Phone: 814.863.2000 ext. 7504. Email: epb6@psu.edu. The Pennsylvania State University. 3400 Discovery Road, Petersburg, PA 16669. Eric teaches courses for Penn State on agroforestry. He also conducts research on important non-timber forest products like American ginseng, goldenseal and ramps.

Category: Blog, Food & Farming