Cal Price and the Fabulous Feline Hoax

Pocahontas Times editor (1906-1957) Calvin Price avidly documented panther sightings in the newspaper. Photo from the WV State Archives.

This article was written by Gibbs Kinderman and was first published in Goldenseal Magazine. 16:2;p13.

“Nobody in Pocahontas County has the slightest doubt but that the name of Cal Price will live on forever after he dies, that is if you can find anybody who believes he will die,” fellow journalist Jim Comstock wrote in 1953. “Most Pocahontasites think of him just living on and on like the trees of the forest.” Price was the editor of the Pocahontas Times for over 50 years, and his name indeed lives on.

Cal Price was a hard-core individualist. He liked the format of the paper when he became editor in 1905 and refused to change just to keep up with fashion. In a tribute written at his death in 1957, a Beckley paper called the Times “pleasantly anachronistic”. It went on to note that “It the heart of Cousin Cal and many of his friends or readers, there were three great newspapers in the world, the London Times, the New York Times, and the Pocahontas Times.

And Cal Price was a conservationist, believing that “you don’t grow good people on poor land.” Next to his newspaper, his family and his Presbyterian God, Cal loved the woods of Pocahontas County. As he wrote in 1940, “I have lain with my feet to a campfire so many time I cannot sleep at nights with my feet under covers. This little weakness has been the cause of strained domestic relations in an otherwise happy, blissful household.”

He sang his love of the outdoors in his weekly “Field Notes,” a feature of the Times second page for decades. “I am a hunter and a fisher who kills less game and catches fewer and smaller fish and talks and writes more about it than any other person in the known world,” he wryly admitted.

Cal the naturalist and conservationist made even a bigger mark in the world than Cal the newspaperman. In 1954, West Virginia dedicated an 11,000-acre tract of land in Pocahontas County as the Calvin W. Price State Forest. Cal’s response was a masterpiece of his trademark self-deprecating humor: “I’m sinfully proud of it. It’s not often a man gets his tombstone before he dies.”

Comstock, Price’s successor as West Virginia’s best-known country editor, studied him from across the mountains in Richwood. “He had three famous theories. The first was that no newspaper should accept liquor ads. Second, America’s prime sin was its disregard for precious topsoil. And third, there were still panthers in the West Virginia mountains.”

It was not the black panther of the jungle to which Comstock referred, but the great American cat variously known as panther, mountain lion, or catamount. That panthers still roamed the Pocahontas woods was more than a theory for Cal; it was an article of faith. And despite the university professors who claimed that the last panther in West Virginia was shot in Randolph County in 1859, panther sightings appeared in the columns of the Pocahontas Times with religious regularity down through the years.

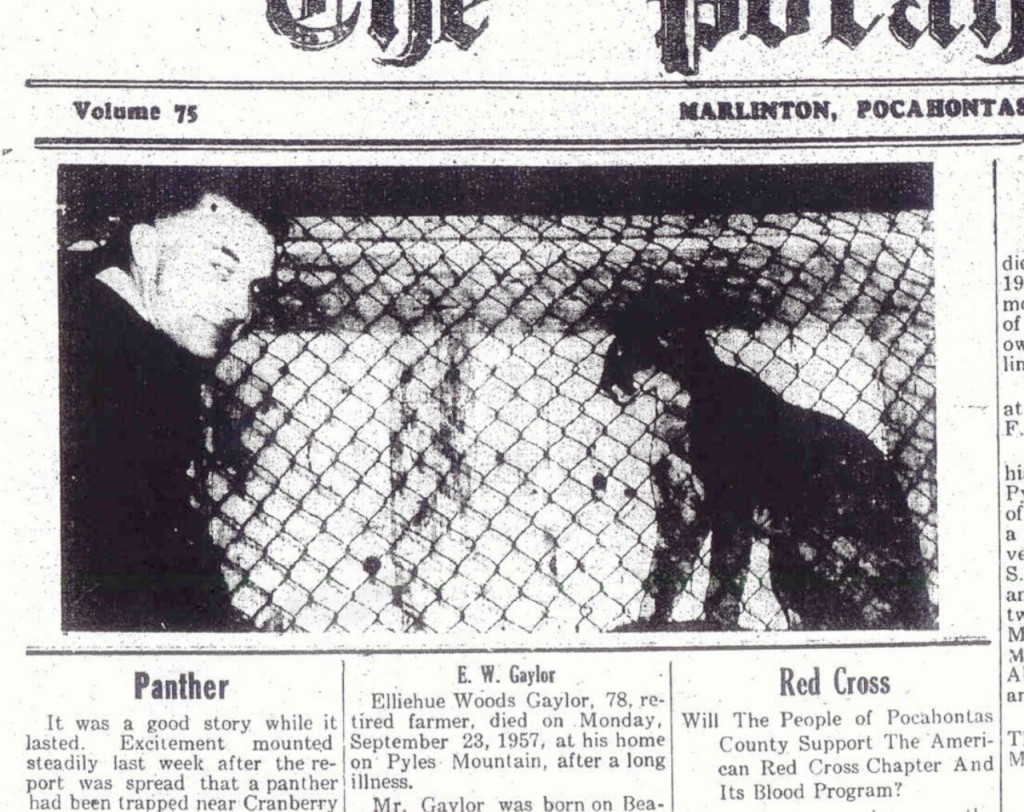

Ironically, the first verified panther sighting in Pocahontas County occurred just a few weeks after Price’s sudden and unexpected death— and it was the product of an affectionate practical joke cooked up by friends of his. Dr. William Birt, a Milton dentist, purchased a mail-order mountain lion from Mexico and enlisted Jim Comstock and fabled Richwood outdoorsman Ed Buck to sneak the beast into Cal Price country. Cal died while the animal was in transit, but the conspirators decided to carry out the hoax as a memorial.

The panther was surreptitiously smuggled into Richwood in a shipping crate, and was duly “trapped” on top of Kennison Mountain, just across the Pocahontas line, by Buck. The fabulous feline went on display at the Richwood Fire Department at 25 cents a peek, and Comstock fired off a special report to the Charleston Daily Mail: “A huge cat measuring about six feet long and standing an estimated two feet at the shoulders was trapped alive yesterday on Kennison Mountain in Pocahontas County, by Richwood high school teacher Ed Buck. C.O. Handley, chief of the fame division if the State Conservation Commission, said in Charleston that the take is unprecedented for this area of the United States in nearly 100 years.” The story swept the state, only to be debunked by the crusading Charleston Gazette within the week.

Had he still been living, Cal Price would have probably enjoyed the prank as much as the next fellow, even though the joke was on him. And it would not have shaken his faith in the Pocahontas Panther one iota. As West Virginia Conservation magazine notes in 1954, “Cal Price believes that if you don’t believe in panthers in West Virginia, then West Virginia panthers will not believe in you.”

Category: Elkins to Marlinton, History, Marlinton to Lewisburg, Panther Tales, Stories & Legends