Nature Train to the Ghost Town of Spruce

After two years of forest restoration work on top of Cheat Mountain, a new tourist train is climbing the old logging tracks to the old ghost town of Spruce, which sits nearly 4,000 feet above sea level. The forests here are returning after decades of timber and coal extraction that nearly devastated the rare boreal ecosystem.

The Cheat Salamander Train, which runs from Elkins, is giving visitors a unique glimpse at this reviving forest, the ghost town, and a piece of history, all in one train ride.

Imagine that you live in a small logging and railroading town on the top of Cheat Mountain. Your dad rises early in the morning, and he hikes a little less than a mile to the headwaters of the Elk or the Shavers Fork of the Cheat River. This was a typical morning for Virgil Broughton. He was born and raised in the town of Spruce.

“He’d go out early in the morning and he’d catch a mess of trout, and we’d eat native Brook Trout for breakfast. With fried eggs or bacon or something like that. I bet you I fished more days than I went to school! There’s no doubt, wasn’t no big deal,” says Broughton.

- The little town of Spruce, where Virgil grew up, once had a hotel, a store, and hundreds of residents. They were tough mountain people, railroaders, cutting trees that were made into lumber and paper. In the 1930s and 1940s, railroaders like Virgil’s dad also hauled coal from the nearby Hickory Lick Coal mine.

I bet you can guess what happened next. Yes, all the timber was gone, and all the coal was gone. And when the jobs fell away, so did the people.

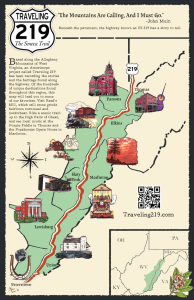

Then something interesting happened. In the 1990s. John Smith, from Philadelphia, opened his own railroad along these abandoned tracks. But not to haul timber or coal, he began hauling people.

They now take thousands of paying tourists remote places within the Monongahela National Forest.

“We’re just trying to bring economic development via the railroad. Cause it’s there, it is making some positive impact here in Elkins, and to some extent in Durbin, but it could be much more,” says Smith.

At least 33 people work on the excursion trains that John Smith’s company owns. People like Mark Phillips, whose uncle worked on the West Virginia Central Railroad, in a previous generation, back when they still were hauling lumber and coal.

“Well I had an uncle that used to work on the railroad. But he’s been passed a long time. This wasn’t a line to run passengers, you know, it was for lumber and coal. Until our company took it,” says Phillips.

What is the appeal to tourists? And why are thousands of people paying money to ride a 9 hour train to the middle of the wilderness, to a place where no human beings have lived since the 1950s? To find out, I joined about 70 passengers aboard the Cheat Mountain Salamander Train train to Spruce. Some locals board the train. But most are traveling here from out of state.

- “I’m Carrie O’Lett, from York, Pennsylvania. We’re here for about two weeks. Just seeing all the sights of West Virginia. We rode Cass the first time out, And this time we picked up Durbin and the Salamander.”

The announcer on board: “We’re heading south to the High Falls of the Cheat River, and then we’ll be on our way to Cheat Bridge, and then we’ll be on our way to the old town of Spruce…..between here and the high falls it’s 1 hour and 45 minutes, so sit back and relax and enjoy our trip…”

The train made a stop at the High Falls of Cheat just before lunch. By the afternoon, we reached our destination, the ghosttown of Spruce, elevation 3,853 feet. I was joined atop Spruce by Rodney Bartgis, state director of the Nature Conservancy in W.VA.

“We are standing at the ghost town of Spruce, at the head of the Shavers Fork. The town was here when they were harvesting the Spruce Forest. Originally this was the largest extent of Spruce south of the Adirondack Mountains. As a result, it is an incredibly rich place to find, even today, things that are typically found farther north. Snowshoe hare and Saw-whet Owl, and critters like that. The Cheat Mountain country right here, which is the two ridges which parallel the Shavers Fork, have more land above 4,500 feet in elevation than all the mountains of New York, Vermont, and Maine combined. At our high elevation, it’s a great opportunity to restore the Spruce up here, and a lot of organizations, the forest service, and a lot of other private groups like ours are involved in that Spruce restoration,” says Bartgis.

And remember those native Brook Trout that Virgil’s dad caught for breakfast?

“You’ve eaten fish. But you’ve probably never ate native Brook trout,” Broughton remembers.

- 11 miles from the nearest paved road, few people have experienced the extraordinary native trout fishing at Spruce. But years of timber and coal industry on the mountain have affected these waters. Scientists today are helping to restore the Shavers Fork to be as healthy as it once was. And they are getting closer.

Bartgis says the Brook Trout, as well as many other native species, like the West Virginian Northern Flying Squirrel, are all part of the rare ecosystem here that once flourished atop Cheat Mountain. “And what they’re trying to do now with things like those stone structures in the river and planting Spruce trees to shade the river, they’re hoping to improve what’s a good trout fishery and turn it back into a great trout fishery,” says Bartgis.

The Ghost Town of Spruce once had a hotel, a store, and hundreds of permanent residents. Today, not one of the buildings remains.

Many streams flow beneath the railroad tracks on their way onto the Shavers Fork. And so for the last two years, these train tracks to Spruce were closed to tourism trains. Meanwhile, biologists with the DNR and WVU have been busy reconstructing some of the streams and culverts. Two years later, the trains are running again, and the brook trout? They’re doing great.

“And so, you know, it’s not just trying to bring back the trees, it’s trying to bring back that whole landscape collection of ecosystems that were up here”, explains Bartgis.

[Song, Little Rose, by the Black Twig Pickers]

So how do people fit into that ecosystem? Because as the forests here, and the native animals, are making their return, so are the people, at least in small numbers. And when John Smith began running tourism trains in the nineties, he learned that a healthy forest can bring thousands of people each year to visit places like Spruce. Both for their human history, and for their natural beauty. Without the trees, and without the beautiful waters, there wouldn’t be tourists aboard this train to Spruce.

There are not many people living who remember Spruce when it was still a town. Virgil has been up to Spruce recently, and I ask him, “What would you like them to see. Or what would you like them to notice?”

“Just the land itself. I never want anything done to it. Leave it the way it is, cause that’s the way it was,” says Broughton.

From the window I could see the Shavers Fork descending the mountain. And we descended too, returning back to Elkins and the modern world.

This story was produced by Roxy Todd. The full version is here:

Category: Blog, Elkins to Marlinton, Roads & Rails