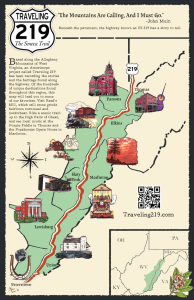

Finding Dewey: The Search for West Virginia’s First Poet Laureate along the Backroads of US 219

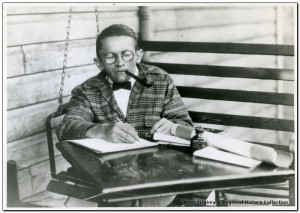

He would write on a green Oliver typewriter, seated on a child-sized armchair with rollers at the bottom. Each day he would write, hour after hour, facing the trains that rushed past him on their way to the Blackwater Canyon. He’d write a poem and if he didn’t like it he would crumple it up, start over again. Day after day. Often, he would drink. It didn’t take but a few beers to drown him because Karl Dewey Myers never weighed more than 60 pounds.

Dr. Walter Barnes, the former Dean of Fairmont State College wrote that Dewey was “absorbed in the basic, eternal problems of mortal existence, struggling to make beauty and truth and mercy prevail.” In his poems, Karl Dewey Myers wrote devotedly about Tucker County, with a sensitivity to its graceful, changing beauty. He wrote of the forests transformed by railroads and logging trains, with an awe for both the natural beauty and the momentum that carried the trains up the steep mountains towards the sky.

Sometimes, Dewey’s profound sense of wonder was mixed with bitterness, as he struggled to stay above the heavy burden of grief for the dead (his older brother and mother both died when he was still a teenager). With words, he fought to persevere over the harsh cruelty of being labeled a “cripple” by the human society he craved. With women, he wrote continuously, though he never experienced romance.

But just before the nation fell into its Great Depression, Karl Dewey Myers was offered a short stint of fame. On June 9, 1927, he was named the first poet laureate of West Virginia.

Cindy Karelis, graduate student of History at West Virginia University, first drew my attention to the story of Karl Dewey Myers. Like me, she had never heard of the poet when one day last fall she found countless writings by Dewey when she was researching the archived writing from the 1930s done by the Federal Writers’ Project. A Tucker County writer for the FWP, Gordon Shrader, knew the poet personally and included Dewey’s poetry in many of his reports. The FWP was a Depression era, federally funded program which employed out of work writers and teachers to complete local guides to their communities.

Like many who befriended the small poet, Gordon Shrader was known to have carried Dewey on his back, literally, transporting him on adventures into the poolrooms of Parsons. For a brief period of time, Dewey lived with Gordon and his family. It was one of dozens of homes offered to the poet, a places of refuge. Beginning in 1932 when his father died, Dewey lived a somewhat transitory life, dependent on his hosts in more ways than he liked. His mother, who had helped him become as independent as possible despite his handicap, had died in 1923. And though many people invited him to stay, Dewey usually wasn’t welcome anywhere for more than a few months, for however long as his hosts could put up with his acrimonious fits of temper and alcoholism.

In 2012, Cindy and I traveled to Porterwood, West Virginia, in Tucker County, to interview 88-year-old Dave Strahin, who is probably the only living person today who was good friends with Karl Dewey Myers. Our conversation was joined by crates of baby chickens, just arrived in the mail. Photos covered the coffee table, piles of them scattered like decks of cards.

Dave turns to us and he says, “Oh please tell his story. Somebody’s just got to tell his story.” In his lap, he searches through a dusty hardbound book, Homer Fansler’s A History of Tucker County. Dave, Homer and Karl Dewey Myers, or “Duke”, as Dave refers to him, were close friends for years. But perhaps nobody was closer to the poet than Homer.

After a few minutes, Dave finds a chapter written by Homer about “poor old Duke,” and hands it across the kitchen table. “Homer and Duke had been friends for an awful lot of years. I guess since the time they were kids. When Homer was still in service, after WWII, he’d go and hunt Duke up and see him,” says Dave. “Poor old Duke, and poor old Homer. They just pitied each other, as all good friends do. Him and Duke used to sit down and laugh about the things they got into. It was fun to sit and listen to those two.”

Childhood friends, Homer often carried Dewey in his arms or by piggyback throughout the fields and forests of Tucker County. As teenagers, they organized a local fraternal organization, which they called the Loyal Order of Tigers, later renamed the Jolly Club. And although Dewey was unable to attend public school due to his handicapped legs, according to Homer he was a self-taught prodigy. Dewey could recite the United States Constitution and the Declaration of Independence from memory, as well as a number of other historical and literary writings.

As they grew older, most of the Jolly Club left for World War II, including Homer. Neighborhood children were often drawn to visiting Dewey. According to local accounts, he was adored by almost all children and animals. But on days when he’d been drinking too much, the parents in town would call each other with a warning. Then all the parents would tell their children, “You can’t go see Dewey today.” Carol Sue Carr, who was a child in Hendrix where Dewey lived for many years as an adult, told us that she never knew what happened when her mother came to tell her that Dewey was “unwell”. Was he violent, gruesome, belligerent, or sick?

To Carol Sue, this only added to the mystery and awe the children felt for Dewey. He radiated a sense of being that dies away in most people as they grow old. And he could speak! He could describe the water and the legends of the woods with such words and phrases, nothing like listening to a teacher or a parent. Yes, he could speak. And those stories stuck with the neighborhood children. They could sit and listen to him for hours. But not on the bad days, which there were more and more of, as the children got older. Then at some point, he just went away. The kids were older then and hadn’t been to see him much lately. And she doesn’t remember where he went, but it was just that he was gone, and nobody was ever like him again.

In 1951, Karl Dewey Myers made a pact with Homer Fansler that each would write the other’s biographies. At the time, Homer was stationed in Tacoma, Washington. On November 29th of that year, Homer received a package from Dewey; it was the biography he had written about Homer. The next day, Homer read of his friend’s death in the Parsons newspaper. Very likely, the biography that Dewey wrote about his friend was his final piece of writing.

Karl Dewey Myers, who died from complications due to alcoholism, was 52 years old. The former poet laureate died without a dollar to his name, with only his small green typewriter, his journals, and two published books of poetry. He passed away at the home of Mr. and Mrs. White just outside of Elkins. He was buried in the pauper’s grave at the I.O.O.F Home in Elkins.

Dave Strand said it took Homer years to complete A History of Tucker County. One of the main reasons, Dave thought, was that he still had one last chapter that sat in his files incomplete. It was the biography of his best friend Dewey. But one day Homer was diagnosed with a very severe case of Leukemia. Doctors gave him just months to live. He had to finish the book now, or never.

All writers know the reason it took him his entire life to write this final chapter of his book, because friendship is never finished. Even when the person has passed away, there is the sense that you will still see them, that they are still alive someplace, that you will make time for them somewhere, somehow. Homer and “Duke” were that type of friends.

In the brief biography, Homer wrote that “the State of West Virginia should be interested enough in its gifted writer and first poet laureate to erect a simple plaque at his last resting place.” Dave says that just before his death Homer even donated money to help pay to have his friend exhumed and moved to his family cemetery in Moore. Shortly thereafter, in 1963, more people became interested the project to moved Dewey to his family cemetery, but the poet’s body could not be found. It seems that nobody had kept records of the placement for the bodies that had been buried in the pauper’s grave, so there was no way to know just where he was buried. From the pauper’s grave in Elkins, they scooped up a bucket of dirt as a symbol of Dewey and transferred that to his family’s cemetery in Moore. The community built a monument at the Myers family’s cemetery, which is located just off U.S. 219.

In 1990, the Tucker and Randolph County Historical Societies revived the quest to locate the exact grave of Dewey, but they too proved unsuccessful. They placed another monument, this time at the I.O.O.F. cemetery in Elkins, in his honor, though it is just an approximate resting place for West Virginia’s first poet laureate, Karl Dewey Myers.

A poem by Dewey:

The Seneca Trail

(Route 219)

By Karl Dewey Myers

I

Where the red men swung with a stealthy stride

Through the endless oak and pin a-row,

While sharp eyes swept each rod they stepped

For the wary game or the lurking foe,

Giving the title of “Warrior Road”

To the lane that ran for a thousand miles,

In the days of old adventure bold

When it filled anon with the dusky files,

With the mad war-whoop or the friendly hail –

This was the Seneca Trail.

II

Where a purr of engines never ides,

And a hurry of wheels is never gone

From a belt of gray that stretches away,

Broad, smooth, beckoning on and on

From bustling village to clanging town,

Through fruitful meadows and vales of dream;

In arrowy flights to conquered heights,

And over many a harnessed stream;

By mine and quarry and burdened rail –

This is the Seneca Trail.

Poem by Karl Dewey Myers, Cross and Crown (1951, no publisher given, page 37).

Category: Blog, Deep Creek Lake to Elkins, History