The Fairfax Stone and West Virginia v. Maryland

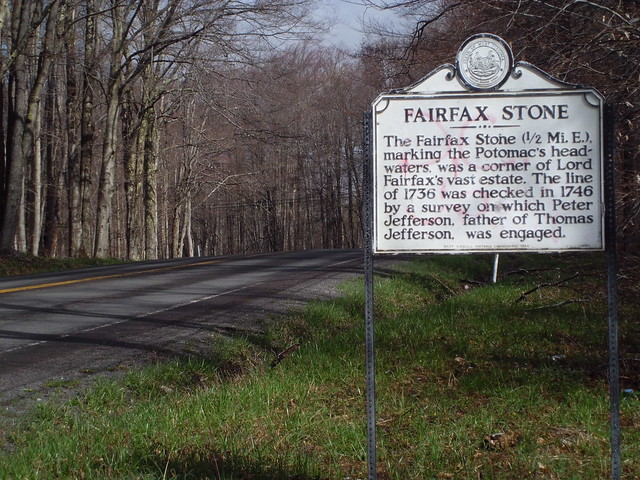

Most West Virginians and Marylanders aren’t aware they share one of the most famously contested state borders in the country. If you’re driving along US Route 219 in Tucker Co, West Virginia, near the Maryland line, you’re bound to pass by the turnoff for the Fairfax Stone Historical Monument State Park, which lies at the origin of this controversy. The western Maryland boundary line with West Virginia was such a controversial issue that the dispute was taken all the way to the Supreme Court, which had to make the final decision on the border in 1910. The West Virginia Surveyors Historical Society has been conducting a number of new surveys in the past two years, uncovering some of the lost history that played an important role in the landmark case between the two states.

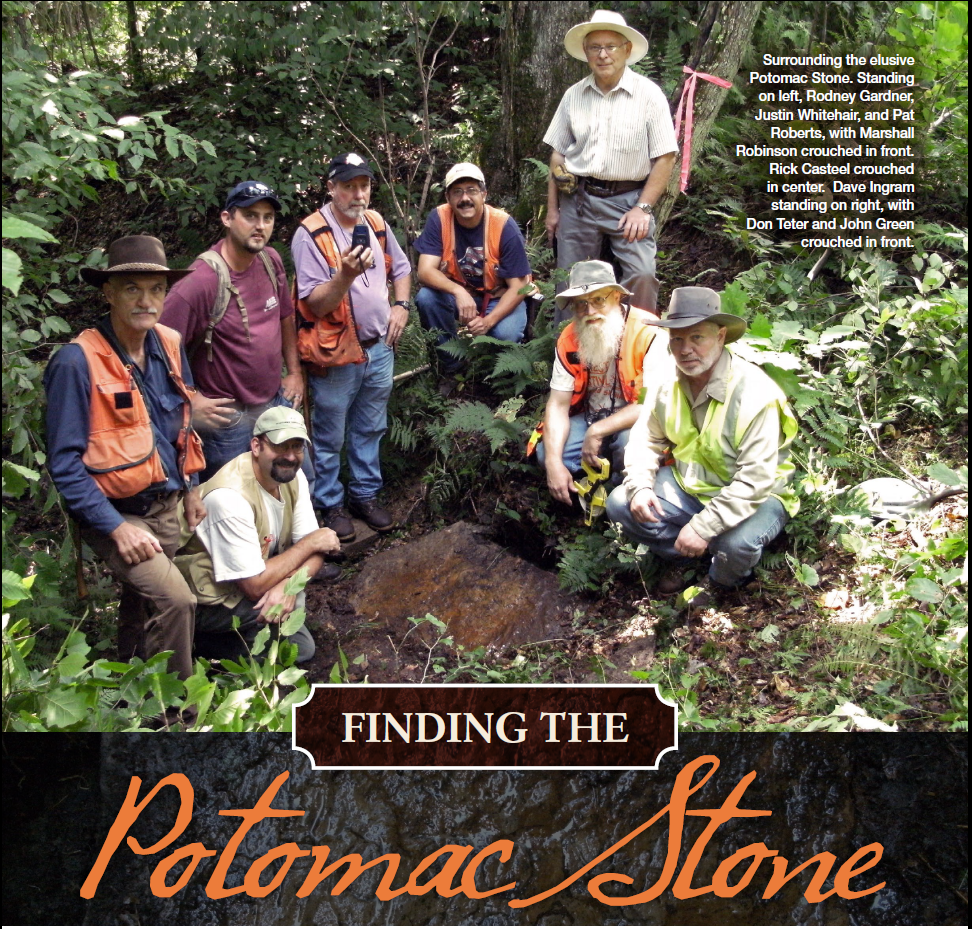

The West Virginia Surveyor’s Historical Society during their explorations. The magazine The American Surveyor featured an article which tells their story of “Finding the Potomac Stone.” Click the photo for the article.

On a chilly September evening I met with Don Teter and a surveying crew who are camped out 20 minutes from the Fairfax Stone Historical Monument State Park. The Fairfax Stone was originally placed to mark the headspring of the Potomac River, and thereby the western border of Maryland with Virginia—and later West Virginia.

“I’m Don Teter. We’re camped here with the West Virginia Surveyor’s Historical Society. We’re camped here at Blackwater Falls State Park campground,” explains Don. The campground is about a 20 minute drive from the Fairfax Stone, which sits just off U.S. Route 219 on the Maryland – West Virginia border.

The Fairfax stone is about the size of a refrigerator, and has plaque on it explaining that the stone marks the headspring of the Potomac River. So, why is this important? Well, as it turns out, the monument probably doesn’t mark the true headspring of the Potomac.

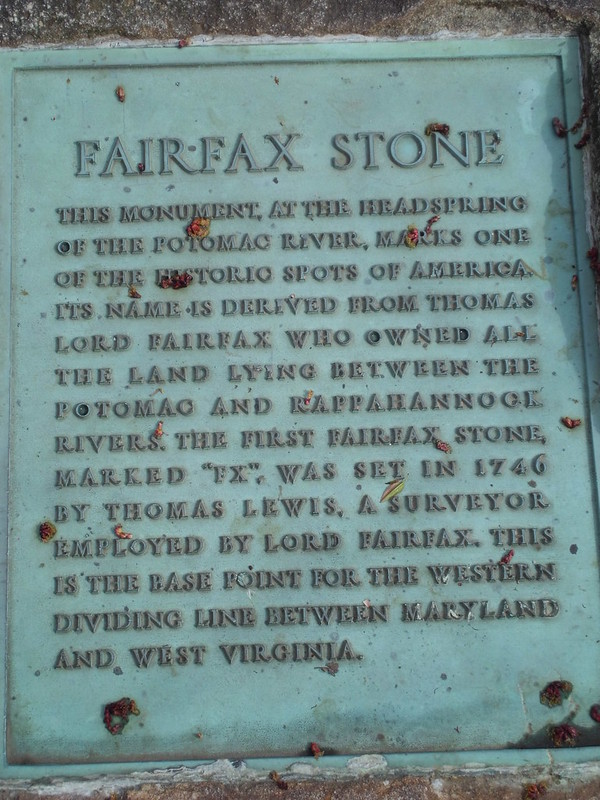

1957 monument plaque, explaining that the Fairfax Stone marks the headspring of the Potomac River. The original Fairfax Stone was placed in 1746.

Way back in the 1730s, the highest court in Britain, which ruled the American colonies at the time, ordered a survey crew to determine where the Potomac River began. This was done on account of Lord Fairfax, who had been granted all of the land between the Potomac and Rappahannock Rivers, and was naturally eager to stake his claim.

Dave Ingram, a member of the West Virginia Surveyors Historical Society, explains how the expedition unfolded: “What happened was the survey crew went out, started out about Harper’s Ferry, as best I can tell, and started going upstream and every time they came to a major fork in the river, they decided whether they were going to go left or right, which stream is stronger. That was their logic for going to the ultimate head stream of the Potomac. They kept on going and going and going and ultimately came out where the Fairfax Stone is located today.”

So, in 1746, a stone was actually placed in this spot, officially marking the western extent of the Fairfax Land grant. Unfortunately, this would set the stage for a future border dispute between Maryland and Virginia, and later West Virginia.

The Fairfax Stone supposedly marked the headspring of the Potomac River, which in turn, marked the southernmost point of Maryland’s western border, which is known as the Deakins Line. By the 1860s Maryland had several boundary commissions formed to re-determine the Deakins Line, which it claimed was not a valid boundary line, because it was neither a straight line, nor had it ever been officially surveyed. The border dispute was not settled before the Civil War came along, and so the new state of West Virginia inherited the issue. Decades passed, and Maryland continued to dispute the Deakins Line as the official boundary between western Maryland and West Virginia.

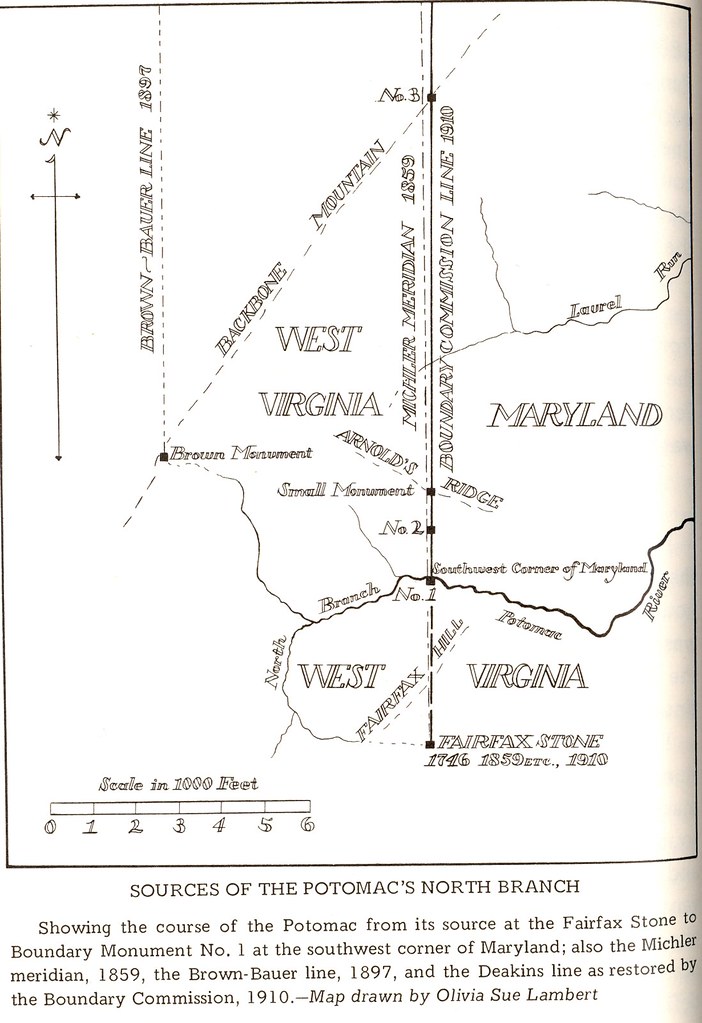

Drawing showing the positions of the different boundary’s and monuments on the border of West Virginia and Maryland.

“So eventually, all the efforts to resolve it broke down, and that’s when the 1890s law suit was filed and of course it took almost twenty years for the law suit to finally work its way through, which is typical of that kind of litigation. It really drags out,” says Don Teter. So the lawsuit went to the US Supreme Court, which arbitrates disputes between states. “In the meantime West Virginia was surveying, Maryland was surveying. They were measuring the various different streams, they were measuring the elevations of the different springs, making arguments for where the true headspring of the Potomac was.”

So while the lawsuit wound its way around to the Supreme Court, Maryland decided it would find the true headspring of the Potomac, and supposedly, the Maryland surveyors found it.

“Well, the Potomac Stone was where the surveyor for Maryland, William McCollough Brown, claimed the true head spring of the Potomac River [was]. He called it the Potomac Spring. He surveyed in the 1890s, finishing up his surveys in 1897, for Maryland, to make Maryland’s case that the Fairfax Stone was in the wrong place, belonged further in the west, and that a sizable strip of ground should have been in Maryland instead of West Virginia,” continues Teter.

So now there were two stones signifying two different borders between Maryland and West Virginia. In 1910, thirteen years after the Potomac Stone was placed and 164 years after the Fairfax Stone was set, the Supreme Court finally made its decision on the case, in favor of West Virginia.

The West Virginia – Maryland border. The once disputed Deakins Line boundary (yellow) was finally settled by the Supreme Court in 1910. The above map shows the current state and county border between West Virginia and Maryland. The blue line is the Potomac River, which makes up the northern border of West Virginia’s eastern panhandle. The yellow line is the Deakins Line, disputed between Maryland and West Virginia until 1910. The red dot is the site of the Fairfax Stone.

The 1910 Supreme Court ordered boundary commission, photographed in camp during the survey work. Photo from the West Virginia & Regional History Collection.

“When they did make their decision they said the William McCollough Brown survey could be correct, in regard to the true head spring of the Potomac, which could be at the Potomac spring–the Potomac stone. They also said ‘it doesn’t matter. If you had brought your lawsuit 125 years ago, we might have agreed with you, but we’re not going to change it now, because that’s what the people have been treating as the boundary. They’ve been occupying to that, it’s been recognized, and after something’s been long recognized, you don’t just turn the world upside down to decide to fix it,” explains Teter.

The dispute was settled. The Supreme Court decided that the Deakins Line had been the de-facto boundary for over a century, and it was not going to change because of a surveying error. In effect, this decision solidified the place of the Fairfax Stone in the nation’s history. The Potomac Stone, however, was left to be forgotten, until this past year, when the WV Surveyors Historical Society got together and found the stone using the original survey notes they unearthed in the Maryland State Archives.

The West Virginia Surveyor’s Historical Society is now working to recover the Potomac Stone and preserve it for posterity. It’s hard to believe that events set in motion before these states even existed could cause a dispute that lasted into the next two centuries, which is still captivating people today. I asked Dave Ingram how someone like himself gets interested in a project like this.

“I’m a land surveyor from Virginia, and got involved or interested in this a long time ago, when I got interested in the Fairfax Survey. That then branched off into working on the Deakins Line and all the various iterations of the Fairfax Stone north. And I just get intrigued by this stuff and dig into it and won’t let it go, and this is from a guy who in high school in college, my least favorite subjects were foreign language and history, and now I like history!”

This map shows what the Maryland-WV border could have looked like. The red is the Deakins line and the current border. The blue solid line shows what it could have been had the surveyors correctly found the true headspring of the Potomac River!

The Fairfax Stone Historical Monument State Park. Pictured are the 1910 monument (foreground) placed by the Supreme Court ordered boundary commission and the 1957 monument with plaque (background).

The spot the original land surveyors for Lord Fairfax thought was the source, or headspring of the Potomac River is still marked and today is maintained as the Fairfax Stone Historical Monument State Park, in West Virginia. It can be accessed from County Route 9, three and a half miles north of Thomas, W. Va. on Route 219.

For more information on the Fairfax Stone Historical Monument State Park, visit: http://www.wvstateparks.com/Brochures/Fairfax_Stone.pdf

A special thank you to Don Teter, Dave Ingram, and the West Virginia Surveyors Historical Society who made this story possible.

Category: Blog, Deep Creek Lake to Elkins, Stories